Get exclusive shortlists, celebrity interviews and the best deals on the products you care about, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Doran Binder has grown used to people responding to his Instagram posts to call him all sorts of names. “Seriously, people get in touch to call me a prick and the like, as though I’m trying to con people,” he says.

“I don’t mind because it means they’re thinking about the subject. They wouldn’t bother otherwise”. Binder’s outrageous claim? That natural waters all taste differently to each other. And certainly to bog standard tap water.

“There’s something triggering about the topic for some people,” laughs Binder, the founder of Crag Spring Water. He reckons that’s because, in the UK at least, we’ve grown used to the idea of water coming out of a tap, on demand, for free (kind of).

A post shared by Doran Binder (@beardedwatersommelier)

A photo posted by on

“Then it’s true that a lot of bottled water is borderline scamming - it’s refined, processed tap water sold back to people at a huge mark-up. And we do need to get beyond natural waters sold in crystal bottles or with gold flake in them. Gimmicks like that. So there are challenges. But there’s also a whole world of amazing natural waters out there to try”.

Binder is one of a growing number of ‘water sommeliers’ around the world trying to get us to take water seriously, “because waters are so very different,” he insists. A water may be low in salinity or high in minerality, for example. If distilled water has a zero rating for TDS (or Total Dissolved Solids) a natural water might be rated at anything up to 30,000 parts per million. It may have a naturally high oxygen content or notably fine bubbles, for extra ‘mouthfeel’. A high level of calcium will give a water the feel of creamy richness, a high level of silica smoothness.

A tap-water terroir

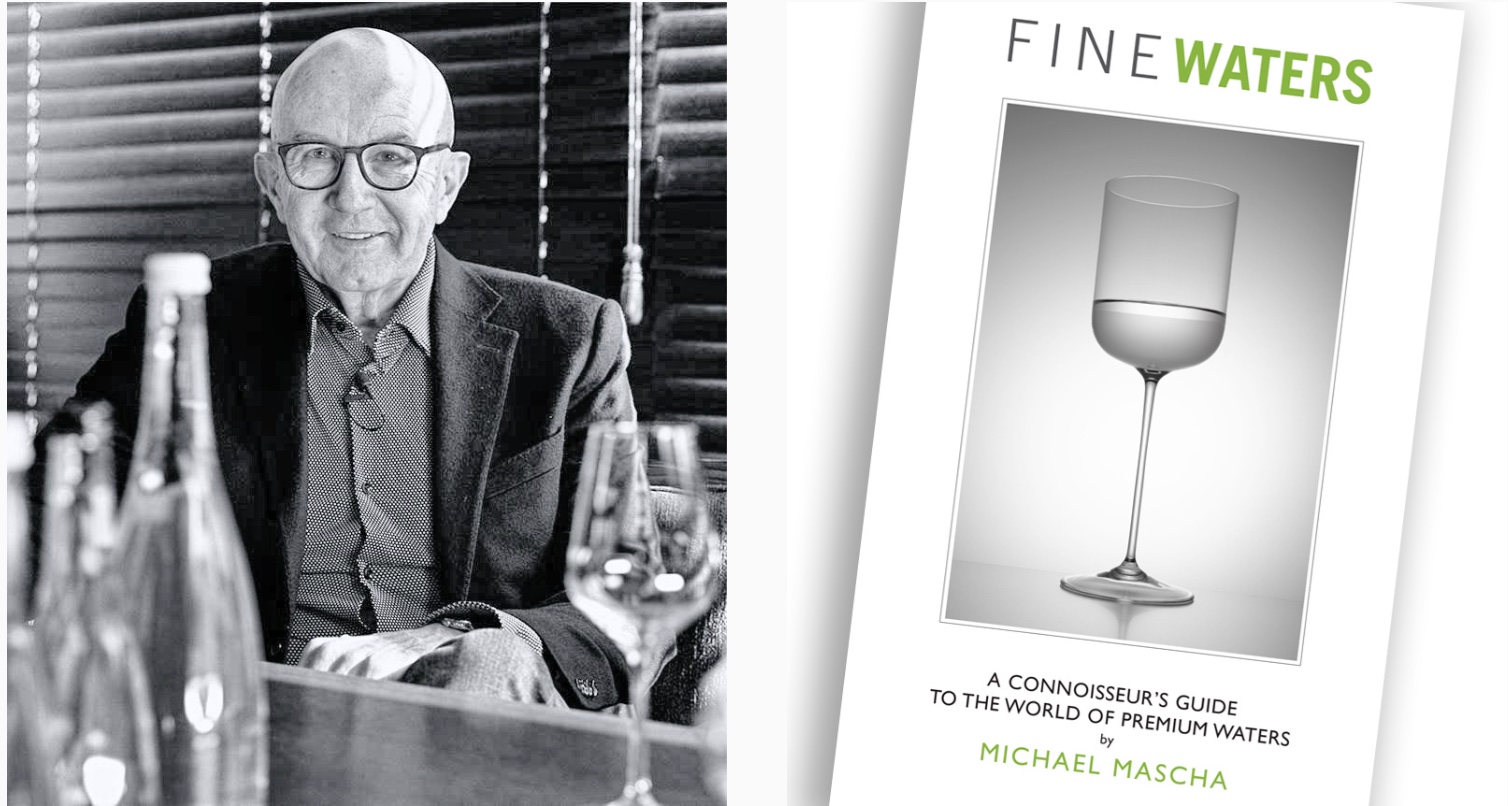

Indeed, according to Michael Mascha (founder of the Fine Water Academy, an international training organisation on natural waters), there’s a creeping acceptance that, of course, water has terroir, as wine buffs refer to how a product, and its taste, reflect a connection to the land. And that it needs explaining as much as it does for a wine.

Look for the origin information on the label, he suggests first. Then look for mineral content — generally the longer the water has in been the ground the higher the content. But also pH level — the higher the acidity, the more sourness; and carbonation, which is often very subtle. All play a part in determining a water’s particular taste.

Get exclusive shortlists, celebrity interviews and the best deals on the products you care about, straight to your inbox.

Michael Mascha, founder of the Fine Water Academy

He compares the best of the natural waters available as something akin to a product provided by local farmers attuned to the earth, to seasonality, while volume waters are pumped out — literally and figuratively — by agri-business giants happy to over-extend aquifers for profit.

Are the former worth paying for? Is the hype around some waters — taken from icebergs frozen for millennia, or from sacred springs deep within the Amazon — just BS? No, he says. If they’re more expensive that tends to reflect the cost of shipping. They will nonetheless have their own flavours unique to the land from which they come, but also something that goes to make a great wine as well — story-telling.

“The wine industry speaks of where its product is from all the time. It’s a way to connect us emotionally to the product, from source to glass,” says Masha. “

Tell people their water is 4000 year old rain that’s been locked in ice and is now on their table and that’s really interesting”.

Big Water vs the independents

That’s important too because most high-end natural water companies, like most vineyards, are small, independent companies that don’t have huge marketing budgets to get across to the public quite why their water is worth a try.

“That’s especially not easy online,” says entrepreneur Jamal Quereshi, founder of Svalbardi Polar Iceberg Water.

“You can’t just make claims to be the purest and stick a picture of a mountain on your label. It’s a slow process of education that’s going on. But the fact is that if you sit down with someone one-to-one to try various waters, it’s incredibly easy to convert people to understanding their different qualities.”

According to Timo Bausch, also a water sommelier and founder of Germany’s Sommcademy, the growing interest in health and wellness may provide the spark that ignites enough curiosity to get people to try just that. Younger generations are drinking less alcohol; we better understand the importance of hydration; and, as had been understood since Roman times, natural waters also provide a critical mineral content you might otherwise have to be more conscious about getting through diet or supplements.

Different waters' different mineral properties have proven - if often slight - medicinal advantages for certain conditions the likes of heartburn, constipation and muscle cramp. But what he’d like to see is more restaurants pairing water with food, or with coffee, or with wine.

He suggests, for example, that red wine works better with a still water because carbonation tends to increase bitterness; whereas light carbonation will underscore the flavours of a white wine. A water high in calcium will have a distinctive saltiness to it that can cut through sweetness; the opposite is true of a water high in magnesium.

“But just having more options for water in hotels and restaurants - not just tap water, not just something you could buy in the local supermarket - opens people up to that idea, which really isn’t such a strange idea,” he says.

It’s not a strange idea, Mascha adds, when we’re seen this process happen before with other goods that we once considered basic and not worth much thought.

Chlorinated tap water was one of the great health interventions, but its place is in giving hydration, not in giving an experience.

Michael Mascha, Fine Water Academy

“It wasn’t that long ago when you’d go to a restaurant and the wine option was ‘red or white’,” he says. “Now we have specialists there telling you about a long list of wines”.

Much as some once very expensive products have become commodities - the likes of sugar, tobacco, spices, tea - so other products once considered to be commodities have undergone a process of artisanal reappraisal. That's not just wine, but also olive oil, salt, chocolate, bread, and so on. Now it’s natural water’s turn. The challenge is getting the hospitality industries to grasp the idea.

“Don’t get me wrong - chlorinated tap water was one of the great health interventions, but its place is in giving hydration, not in giving an experience, and that’s what a natural water can do, much as we now understand that a great olive oil makes a difference too,” says Mascha.

“Unfortunately, getting that distinction across is taking time, not least because beverage managers [in bars and restaurants] are lazy. They’re making money with wine so thinking ‘why bother expanding the offer?’

"And that’s even as we drink less and less of the stuff they want to sell us. But it will happen for water. I give it five years - and then this conversation won’t seem so strange to a lot of people”.

Skip the search — follow Shortlist on Google News to get our best lists, news, features and reviews at the top of your feeds!

Josh Sims is a freelance writer and editor based in the U.K. He’s a contributor to The Times (London), Esquire, Robb Report, Vogue and The South China Morning Post, among other publications. He has written on everything from space travel to financial bubbles, and art forgery to the pivotal role of donkeys in the making of civilisation.

A former editor of British style magazines Arena Homme Plus and The Face, Sims is also the author of several books on style including the best-selling Icons of Men’s Style. He’s married and has two boys. His household is too damn loud.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.