Get exclusive shortlists, celebrity interviews and the best deals on the products you care about, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If you’d like to go and put on Bill Elm and Woody Jackson’s soundtrack to Red Dead Redemption right now, that’d be cool. We’ll wait.

You tramp up the hill that leads you to a cliff-edge that overlooks Lake Don Julio in Cholla Springs, New Austin. Whistles and a sort-of broken, melancholic violin plays. Your horse pants loudly; its suede flanks rising and falling. Orange plumes of dust rise up from whence you came...

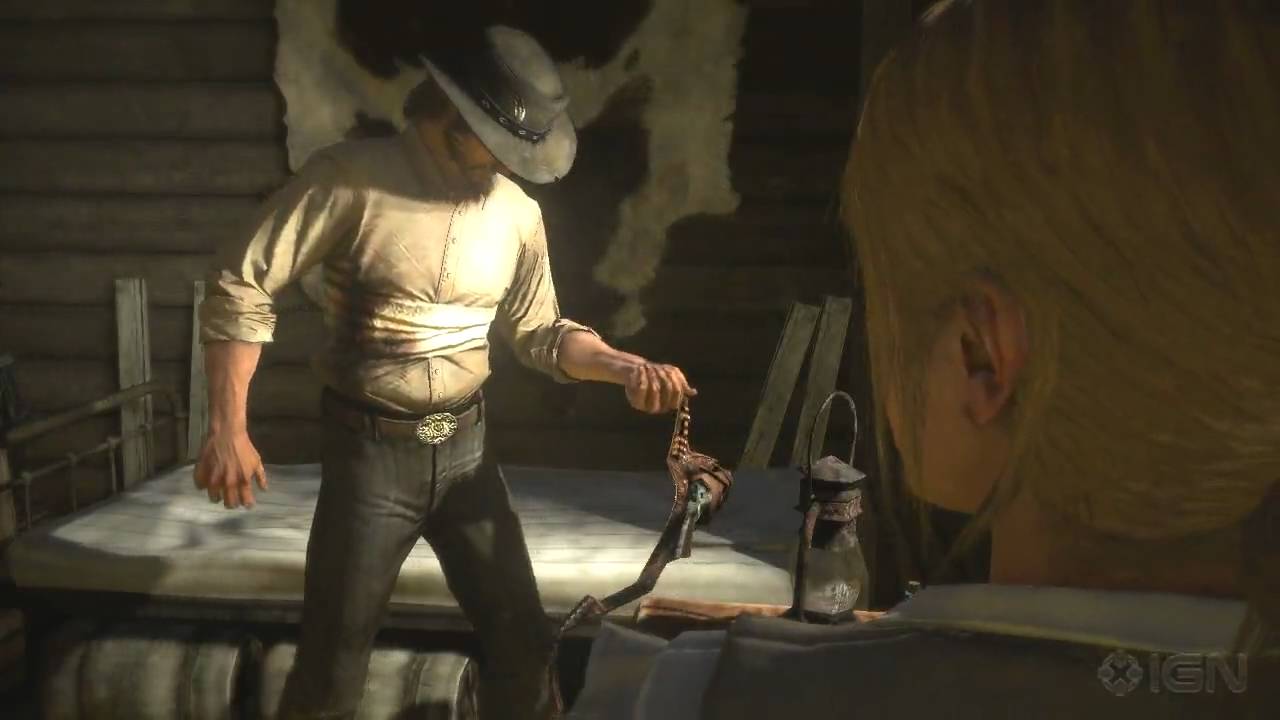

In Red Dead Redemption, Rockstar Games’ crack at Deadwood-meets-Grand Theft Auto, you are John Marston: reformed fucker and a previously-reformed fighter.

Dragged away from your family and into violence once more, you spend your long days killing bad men with bad breath, black-hatted bandits, evil gravediggers, corrupt politicians, and any animals you can find, stripping them bare of their meat and pelts.

The landscapes you wander are barren. The locals are duplicitous shithouses. You hate everyone and everyone really hates you. The wild animals want to kill you. The horses are unruly and temperamental. The guns are slow and often ineffective. You are perpetually alone. It’s brilliant.

Maybe it shouldn’t have worked. At the time, nobody was calling out for a sandbox game about the Wild West, let alone a a sequel to a game, Red Dead Revolver, that nobody remembered.

Looking back though, it makes me think a lot about Skyrim, which came out the following autumn. Like Skyrim, Redemption managed to elevate loneliness to an art form. They made isolation the game’s Big Bad, its main antagonist.

Get exclusive shortlists, celebrity interviews and the best deals on the products you care about, straight to your inbox.

When the game came out, I was nineteen. Single and working night shifts at a shitty job that I hated, I knew a little bit about loneliness. Coming as I readied to leave my teenage years behind, this game about the last days of the Wild West struck a chord.

Maybe I thought I was like John - only without the murder, without the pelts, without the rifles. John’s fears mirrored my own - what was this strange new world? Would it be better? And what were all these horseless-carts about? It all hit me like a buckshot to the gut. Living vicariously through this man who just wants to understand this world that hates him made me feel like my heart was about to fall out my backside.

I was soon drawn to sitting on my own, wandering the game in a daze, Ennio Morricone-ish noise filling my room. Skint, I’d happily skip more than the occasional night-out to wander Armadillo or murder my way around Fort Mercer. Unexpectedly, my dad’s interest was finally piqued by a video game. In fact a fair portion of my weekends would involve him trying to talk me into watching Rio Bravo or The Searchers or, his favourite, High Noon.

Sometimes he’d pop his head into my room under the pretense of serious-father-stuff and we’d just sit together, in silence, and trot across the game’s map. These were sweet, precious moments between father and son, only occasionally punctured by my dad shouting “Quick! Shoot that c*nt!” or “Sam, skin that horse".

Each time I had to kill an animal - a bear, a charging buffalo - I’d get a wince of real pain. Just a little one, but it registered. That had never really happened to me in a game before: I felt a genuine remorse for my actions. I’m not even really an animal fan.

But kill I did, firing at these pixels, causing other, redder pixels to spurt out of them and becoming near hypnotised. I’d become so intrinsically linked to the nature of the game, its changing seasons, the game’s finely balanced ecology, that killing an animal felt so much worse than trudging my way through the storyline and murdering a few cock-eyed sheriffs.

Admittedly, for all the beauty, sometimes it really was a slog to get through the story. One aspect of the game nobody ever talks about is the plot, which is handy because it was generally lame. As ever with Rockstar, just one long introduction to the world. Ride here, kill this, blow up that.

But still, it became a cult classic. Marston and the setting were the true stars. They were the things that kept us coming back, and kept the game in our consoles long after the missions were over. Imagine any eighties buddy movie: Marston is the gruff by-any-means-necessary hard-ass, and his scene-stealing, wise-cracking sidekick is played by a visually pleasing landscape with nightmares running through its myriad forests and rock formations. Cowboy & Vista is a movie I’d watch.

When it was all over, long after THAT ENDING THAT I WON’T TALK ABOUT HERE BECAUSE FUCKING HELL, BUT HERE’S A LINK TO IT IF YOU HATE YOURSELF AND WANT TO RUIN YOUR FUCKING DAY, and the brilliant Undead Nightmare downloadable add-on, its presence remains. Rockstar learned that they could do heart, they could create animals and players learned that there were some brilliant, relevant games to be made from the those old John Wayne films.

Few things move as quickly as video games do, and it's been a whopping six years since the last one, so as the developers saddle up for the sequel, I'll be ready. Or I hope so anyway.

God knows what emotions they can twist and terrorise out of me this time.