Burnout, illness & unhappiness: Why are we working ourselves to death?

The nation spends more time glued to their desks than ever before - and we're suffering the consequences

Get exclusive shortlists, celebrity interviews and the best deals on the products you care about, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

How’s your week going? Busy?

Of course it’s busy. As a bee. As a beaver. As a caffeine-addled blue-arsed fly. Boss on your back, no doubt. Your to-do list is looking so long and bleak that Lars Von Trier wants to turn it into a film. Burning the candle at both ends? You wish. Your candle looks like it’s been microwaved. You’re not so much chained to your desk as calling it ‘master’ and letting it walk you round the office on a lead.

Well, join the club. We’re all busy. Or at least, we all claim to be. “Ask someone what they’re doing and no one ever says, ‘Oh, I don’t actually have a lot on, I’m very relaxed,’” says Sir Cary Cooper, professor of organisational psychology at the University of Manchester. “They’ll say, ‘I’m overloaded’ even if they have nothing on that day.”

Busyness has become a status symbol. Free time is for unimportant people, so weekends in the office go straight on Instagram. “This pride [in workaholism] is so sad,” says Cooper, “and it scares me.”

It should scare you too, because his research shows that in every country, across every demographic, working too much makes you sick. “You will get either physically ill, such as having a heart attack, or you’ll have a mental-health problem: depression, anxiety.”

And yet odds are that your relationship with your desk only trends in one direction.

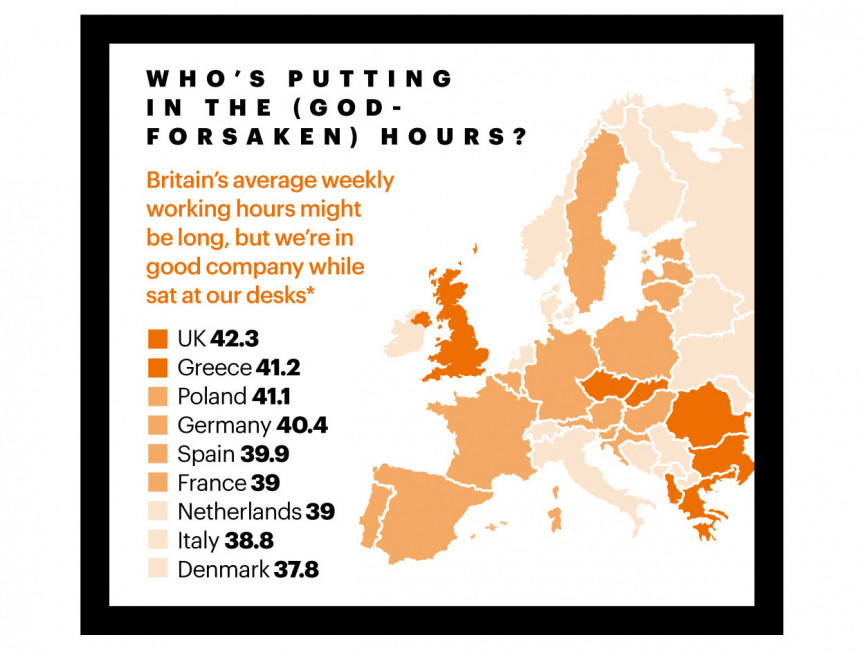

Brits work some of the longest hours in Europe: more than 42 a week, on average, compared to Denmark’s 37. We’re also among the fattest, the most at risk of heart disease and the most crippled by back pain. These things are not unrelated: when you work more, you move less; when you move less, you get sick.

Get exclusive shortlists, celebrity interviews and the best deals on the products you care about, straight to your inbox.

You may also like

We spoke to a bouncer, marine, and prison officer to find out what it's like to be tough for a living

“Sitting may be linked to a range of complaints, from back or neck aches and pains to cardiovascular disease and even depression,” says Alan Taylor, a professor of physiotherapyand rehabilitation sciences at the University of Nottingham.

Of the time you spend sitting, around 70 per cent is at your desk – more if you’re logging Stakhanovite hours. The World Health Organisation has inactivity at number four on its list of people-killers, coming in above obesity and below elevated blood glucose. So be doubly concerned if your only desk breaks are to raid the biscuit tin.

In a 2014 article, the Mayo Clinic’s Dr James Levine emptied both barrels on your desk chair. “Sitting is more dangerous than smoking,” he said. Levine linked those sedentary hours to everything from diabetes and strokes to cancer. Research has since diluted that media-friendly claim, but even if your desk chair isn’t quite as deadly as a pack of Lambert & Butler, all that time spent staring at Excel is definitely doing you damage.

“The enzymes that transport bad cholesterol out of our arteries and into our muscles to be burned off require 12 hours of minor activity a day,” says Gavin Bradley, founder of Active Working, which runs the Get Britain Standing campaign. “But the average office worker sits for 10 hours a day.”

Most of that comes in what Bradley calls “sustained binges”, which are particularly bad for your health. Your body is designed for constant motion. When you’re still, it doesn’t work properly: research from the US shows that sitting for five hours a day in addition to the time you spend sitting at work increases your heart disease risk by 34 per cent compared to sitting for two hours extra, even if you exercise.

The problems are particularly acute for men, in part because we spend longer at work, but also thanks to the way we’re built. When you switch between sitting and standing, you shunt blood around your body. If you hold one position too long, circulation slows down, which can lead to blood clots and more personal problems. “No blood, no erection,” says Dr Joan Vernikos, former director of life sciences at Nasa. “You probably also damage sperm health and motility. No wonder western fertility has dropped.”

That we’ve let ourselves get into this mess would have blindsided the economist John Maynard Keynes. In 1930, he published an essay that looked at how the industrial revolution had boosted productivity, calculated where that pace of progress would take us and predicted that his grandchildren would only need to put in a 15-hour work week.

In Keynes’ view, humanity was about to face the crisis not of too much work, but too much downtime. “There is no country and no people,” he wrote, “who can look forward to the age of leisure and abundance without dread.” Well, we certainly dodged that bullet. Eighty-five years later, US radio station NPR tracked down his actual descendants to see whether their grandad’s prediction came true, and found they were logging between 50 and 100 hours a week. In that, they were chips off the old block: Keynes died aged 62, after a series of heart attacks reportedly brought on by chronic overwork.

So why do we insist on working ourselves to death? Partly, it’s because hours are easier to measure than output and therefore easier to reward. “Bosses see people who are there from dawn to dusk as being committed,” says Cary Cooper. The Office For National Statistics reports that output (measured in GDP) per hour worked in the UK was 16.3 per cent below the average for the rest of the G7 in 2016 – 26.2 per cent lower than Germany. “We’re burning people out,” says Cooper.

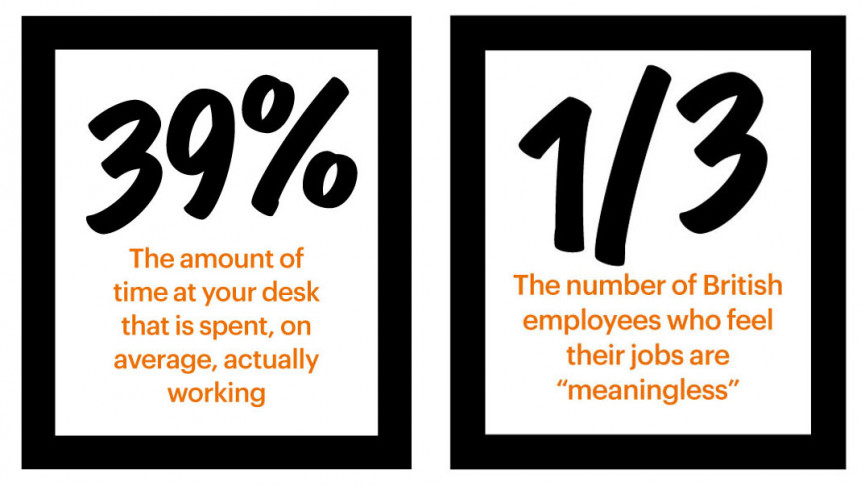

Silicon Valley consultant Alex Soojung-Kim Pang believes that humans can only spend four hours a day doing anything productive, a theory backed up by a glut of studies – and the schedules of those notorious do-nothings, Charleses Dickens and Darwin.

“Bosses see people who are there from dawn to dusk as being committed. We’re burning people out”

It’s harder to pin down precisely when work becomes overwork – if you enjoy your job, for example, you can survive more than someone who dreads Monday mornings – but 50 hours a week is a pretty universal ceiling. “Once you go over that, you’re at danger of overworking yourself,” says Dr Almuth McDowall from Birkbeck, University of London. “Waking up in the middle of the night and thinking about emails you haven’t answered, being irritable with colleagues, getting forgetful or starting to double-book yourself are all clear signs that you’re overdoing things.”

As McDowall puts it, overwork creeps up on you. Its symptoms arise gradually and you don’t realise you’re suffering until it’s too late. That’s because though our bodies have evolved to handle high-stress situations, they break down when those high-stress situations last for months. Your desk isn’t quite a sabre-toothed tiger, but your brain responds to both by flooding your body with fight or flight hormones. When the tiger stops chasing you, they subside. When your to-do list is always chasing you, they don’t.

“If you never switch off, your arousal levels are continually peaking,” McDowall says. Cue everything from anxiety to a depleted immune system and gastrointestinal issues.

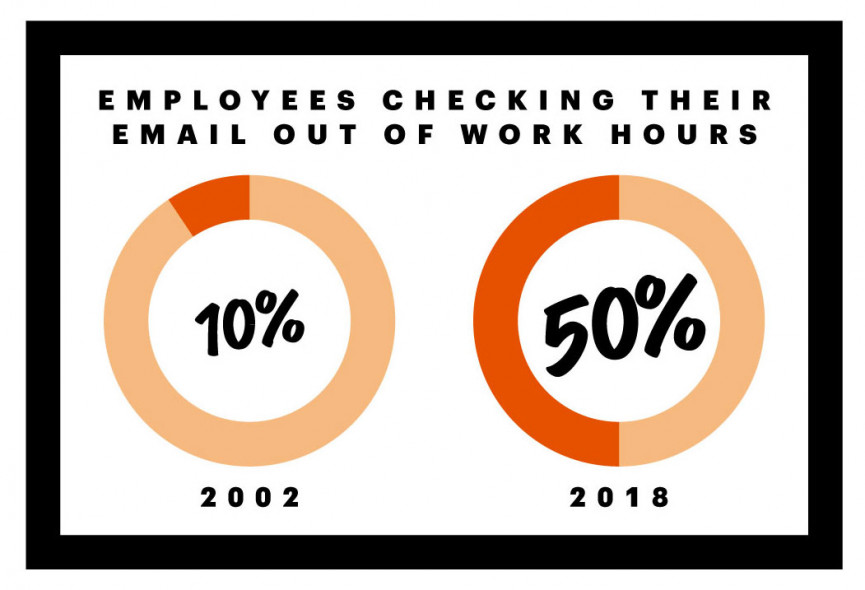

One nice thing about tigers is that they rarely ping you on the weekend asking where the hell those reports are. Half of employees now read emails out of hours, a 400 per cent increase since 2002. It’s so common that for many, emails don’t even feel like work. But when they interrupt dinner or are the first thing you look at in the morning, they get those stress hormones spiking and stop you from focusing on time with your family.

“The technology is damaging,” says Cooper, “and companies don’t have guidelines on what’s appropriate behaviour.” Email has become just another way to show commitment: when your boss emails out of hours, you race your colleagues to respond first.

To stop this kind of nonsense, France made a new law giving workers the “right to disconnect” outside office hours. Volkswagen shuts its email servers outside work hours for some employees, to help workers switch off.

In the UK, we continue to turn up early, do less than we could and leave late, and then send emails on the train home to show the higher-ups that we’re still working.

That those who work longest often climb highest – and sometimes independent of actual performance – creates a self-perpetuating loop. Managers reward overworkers because they got their own promotions through overwork. For men especially, there’s a direct relationship between putting in hours and tangible rewards in a way they don’t get at home. “They’re used to seeking promotion, and the job title being important to them and their identity,” says Cooper. “Home doesn’t give them that. There’s no pay-off other than happiness. They tend to realise that too late.”

So are we going to break this miserable cycle? Cooper is pessimistic about immediate change. “Brexit will create insecurity,” he says, “therefore people will want to show facetime.” But longer term, he thinks that people are finally starting to understand the research because the damage is becoming more visible: “Look how many CEOs have admitted they’ve been suffering from depression. Then younger people look up and think maybe it’s not so rosy getting there; there’s a cost to pay.”

The causes of the problem could also be the solution. Technology has made it easier to work flexibly and to track what we actually get done, rather than simply how long we spend doing it. The nine-to-five is a hangover from industrial ways of working, when everyone needed to be at the factory at the same time. In a knowledge-based economy, people should be free to work when and how suits them best. And companies are finally starting to cotton on.

“Nobody really knows how to manage the way work has changed so profoundly,” says Almuth McDowall. “It’s one of life’s giant experiments.”

A happy worker is a productive worker. A burned-out worker, forced from the office by anxiety and back pain, is bad for the bottom line. “There is no research evidence that shows that working a regular nine-to-five – to six, to seven, to eight – is a good thing. So if we can manage flexibility properly it’s a huge, inclusive opportunity.”

Spending too much time at your desk is crippling you, mentally and physically. But it doesn’t need to. Clear your diary. Close your inbox. Go home. You’ve earnt it.

Get our best stories, delivered daily for free

Get exclusive shortlists, celebrity interviews and the best deals on the products you care about, straight to your inbox.

(Images: AllStar)