Get exclusive shortlists, celebrity interviews and the best deals on the products you care about, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

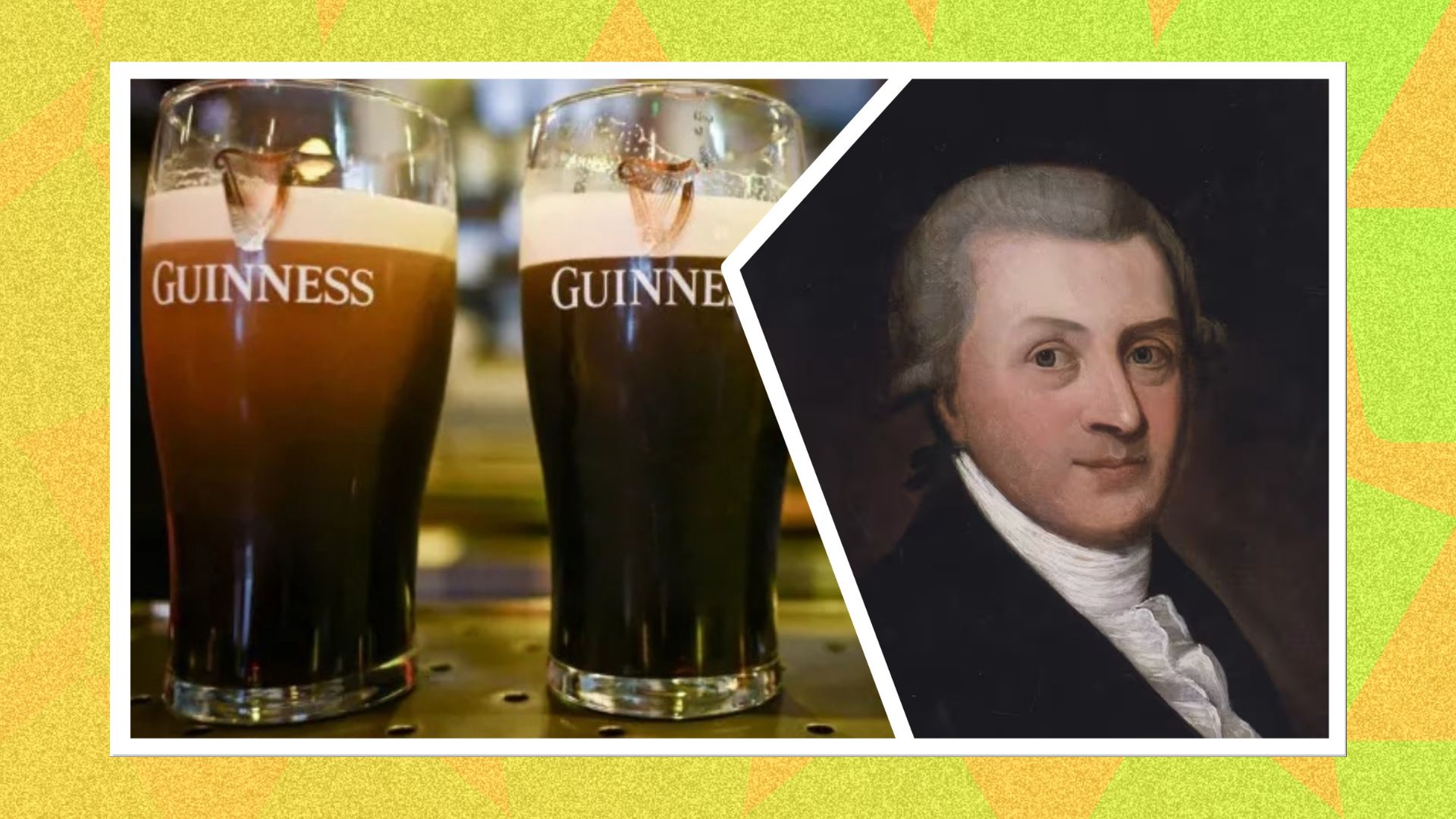

Thanks to its distinctive colours and slow pour, it’s arguably the most easily identified drink in the world, at least for pub regulars. But, of course, it’s not the look that has us drinking over 10 million pints of Guinness a day globally. Its flavour, and that history has made Guinness not just the world’s largest brewer of stout but definitively the stout.

“That can be frustrating when there are many great, in ways more interesting stouts out there that can struggle to be seen above all the noise created by Guinness - it’s just such a marketing juggernaut,” admits Jonny Spanjar, co-founder of Margate’s Northdown Brewery, which makes its own Tidal Moon stout. “But you have to admit that Guinness isn’t just a dependably drinkable stout - which is a drink not everyone likes anyway - but that there’s also something iconic about it”.

A history worthy of its own show

As Netflix’s forthcoming series House of Guinness attests to, the incredible story of Guinness - a drink once creatively marketed to early expectant mothers as supplying part of their daily allowance of iron, and which in parts of Africa, the Far East and the Caribbean is still believed to have a quality akin to Viagra - and of the family behind it is equal in distinction to the liquid itself.

Much as this quintessentially Irish tipple’s relationship to its Irishness has often been less than secure - with one family member, in 1913, funding Ulster Volunteer Force para-military campaigns to resist Ireland being given legislative independence, to, in the 1980s and amid the height of the Troubles, the then owners hatching plans to rebrand Guinness as an English beer brewed in west London - so much that is fact about the family behind it has the air of fiction.

And, given that Arthur Guinness, who founded the company in Dublin in 1759, fathered 21 children with his wife, 10 of whom made it into adulthood, there is a lot of family to give us many an incredibly tall, yet nonetheless true tale of intrigue, scandal and historic machinations. As Jasmine Guinness once quipped, “the truth is, there are so many of us now that there isn’t enough money to go around”.

An eccentric collective

Take, for example, the homosexual affair of the 1830s between Arthur’s son, also Arthur, and a brewery clerk and would-be actor by the unlikely name of Dionysius Boursiquot. This was a contretemps that almost led to the collapse of the Guinness enterprise. Arthur II was given enough money to leave the business, buy a home and live “moderately”, moderately meaning having a blind, white bearded harper visit his mansion every afternoon to sing Irish folk songs in the courtyard - his fondness for the harp perhaps having influenced Guinness’ adoption of the instrument for its logo.

And he was just one of its many creative, wild, independent, oblivious oddballs, some joining the story through marriage, some ending up apologists for Hitler, others sellers of magnetic wristbands of dubious benefit to the arthritic. It has always been a family of self-invention, Arthur Guinness himself included.

Get exclusive shortlists, celebrity interviews and the best deals on the products you care about, straight to your inbox.

After all, Guinness, aged 34, bought a run-down brewing business and produced fairly standard ale for many years: porter, the dark brew that took its name from the stevedores of Covent Garden and Billingsgate Markets, who favoured it, was actually invented in London. Young Guinness merely took an established idea, increased the strength of the brew, and, in doing so, created arguably the beer industry’s first international brand.

“I think that’s one reason why, while there are many stouts out there, Guinness is still just so dominant, in the way that there’s no similarly dominant lager among lagers,” argues Ryan Smith, founder of the online beer retailer Beerhunter. “It’s a legendary sense of branding that has continued, from the likes of the Surfer TV ad to the ‘splitting the G’ drinking game. The fact is that if you go into a pub for a stout on tap, it’s going to be Guinness, which is amazing for a style of drink that’s a bit Marmite”.

Building a community and legacy

Clearly, Arthur Guinness was canny in many ways - less out of confidence in his product than a legal fix to allow him control of his future, Arthur took out a 9000-year lease on his new premises, much to locals’ disbelief. The brewery he bought had been on the market for a decade without a drop of interest.

His vision paid off for many around him, though. Guinness - a protestant in a largely Catholic country - believed that all he achieved was heaven-sent, and poured vast amounts of money into the community, helping, for example, to create Ireland’s first Sunday schools, to pioneer the idea of public recreation areas and the first pensions for its workers - not to mention subsidised daily meals with two free pints of Guinness - and, contrary to the habits of the social class in which his wealth now placed him, spoke out against material excesses.

This community spirit would run through the family. One 19th-century Guinness heir, on receiving £5m as a wedding gift - then far from being small beer - moved himself and his bride into a most insalubrious neighbourhood to draw attention to the plight of the poor, which it did, the papers of the time having a field day with these eccentric antics. Edward Guinness, Guinness’ grandson, funded early polar exploration, scientific research and established the Guinness Trust housing association, which still manages some 60,000 homes today.

But what, one wonders, might Arthur Guinness have made of his ancestors during the Irish Famine, who used most of the country’s barley harvest to produce beer for export - and required armed British guards to ensure the ships left port safely - or which bought up desperate tenant farmers’ abandoned land at knock-down prices?

Too wild for fiction

Naturally, the lineage would produce its share of Playboy types, too. Kenelm Guinness, for instance, would put his money into motor racing, albeit with serious intent. Before he committed suicide in 1937, he had not only developed his own car, won the Spanish and Swiss grand prix, broken the land speed record and designed and engineered a spark plug. This not only revolutionised racing engines, but was found to be so effective in aircraft that Kenelm’s attempt to enlist during World War One was rejected, so important was his work in the new technology considered to be to the war effort.

Certainly, the Guinness clan would often influence geo-politics in ways hard to appreciate now, despite topicality. Take, for instance, Henry Grattan Guinness - Arthur Guinness’ nephew - who re-invented himself as a scholar of Biblical prophecy, his books, including The Approaching End of the Age, foretelling the coming return of the Jews to their homeland in Palestine, in 1917 to be precise. Arthur Balfour, future British prime minister, wrote to Henry in 1903 expressing his interest in his ideas and, lo, in 1917, signed a declaration stating that the government would use its “best endeavours” to bring this about.

Then there is Walter Edward Guinness, Lord Moyne, appointed Minister Resident in Egypt and the British Middle East in 1944 and - in a weird twist of family fate - assassinated the following year by members of Lehi, an extremist Jewish group. Under Churchill’s orders, everyone involved with Lehi was arrested, the assassins were executed, and the cause of a Jewish homeland was arguably put back decades. Such was the intricate web of history over which the black stuff cast its bitter-sweet dew.

Even bit players seem to have incredible stories. Take fashion model and Truman Capote groupie Gloria Guinness, who married into the family via her third or fourth husband - nobody is quite sure - despite rumours, which she neither admitted nor denied, that she had been a German spy during the 1930s. After the war, she married the grandson of the King of Egypt, then met her future husband, Loel Guinness, on a yachting trip on which she’d been invited by his wife.

Or Guinness heiress Caroline Blackwood, who ran off to Paris to marry a then unknown painter by the name Lucien Freud during the 1950s and, when the family disapproved and she broke it off, was propositioned on a rooftop by someone called Picasso.

And on it goes - so many stories, too little drinking time. “That’s one of the things that so many people don’t realise about Guinness - whether you like stout or not, it has just such a fantastic story,” enthuses Northdown Brewery’s Spanjar. “It’s almost more than a beer. It’s part of the furniture of pub life, part of our psyche. And not just on St. Patrick’s Day”.

Josh Sims is a freelance writer and editor based in the U.K. He’s a contributor to The Times (London), Esquire, Robb Report, Vogue and The South China Morning Post, among other publications. He has written on everything from space travel to financial bubbles, and art forgery to the pivotal role of donkeys in the making of civilisation.

A former editor of British style magazines Arena Homme Plus and The Face, Sims is also the author of several books on style including the best-selling Icons of Men’s Style. He’s married and has two boys. His household is too damn loud.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.