Why it’s time to address our unhealthy relationship with comedy

There's a big problem with self-deprecation

When I was 13-years old my school trousers weren’t as long as my legs. I’d also developed a noticeable penchant for wearing white socks.

One kid in the year above me at school developed a recurring act where he’d call me “povvo Michael Jackson”, yell “shamone!” and inform me that I was “moonwalking the wrong way to gay club.” He’d shout this because I was small, runtishly skinny and wore ill-fitting trousers. In the early playgrounds of the early noughties, this was apparently how sexuality worked.

Around the same time my hair also helpfully turned from strawberry blonde to ginger, adding more fire to the secondary school taunts. My usual approach was to maintain a degraded silence, letting anyone with longer limbs and faster fists have their fun. This kid was persistent, though. Sometimes he’d jeer the tune to ‘Beat It’, others he’d grab at my crotch and jeer “hee-hee” until I did “the ‘Thriller’ dance”.

On one occasion, completely forgetting my usual tactics, I didn’t stand quietly when he asked if my mum had bought me new trousers yet. Instead, I retorted: “obviously not, has yours bought you any new jokes yet?”

Taken aback, particularly as his friends enjoyed that comeback, he doubled down and asked why I wore such short trousers, implying once again that this made me gay. With reckless abandon, I said that shorter trousers were tighter, and I was doing it for him, because he loved staring at my cute balls. His pals loved it. He very visibly didn’t, and so I scarpered.

This juvenile (and not particularly edifying in today’s enlightened times) exchange probably wasn’t the Damascene conversion my brain thinks it was, but it bookends a period in my childhood where I was a cripplingly shy and irresistibly meek target, and gives way to one where I became a semi-fearless ‘class clown’.

I could make fun of myself like no one else could, so that no one else could. You’re doing the work of the tormentors for them, and so that, in turn, they respect you for it. Sort of. It’s a defence mechanism, certainly, but it was also powerfully addictive.

Without laughter we would drag ourselves from day-to-day across a punishing landscape devoid of fun, like characters in a Cormac McCarthy novel, surviving, but for what purpose? We need laughter. But how do we want to be made to laugh, and at what, and by whom?

These are all questions that seem worth asking as the Edinburgh Fringe - a month-long festival where hordes of people desperate for laughter are served by hordes of comics desperate to make them laugh - gets underway. They’re questions that seem especially worth asking in the wake of the deafening wave of acclaim for last year’s winner of the Fringe’s Best Show award, Hannah Gadsby’s Nanette - acclaim that grown further since the show was released on Netflix last month.

It’s an astonishing performance, one which definitely warrants watching prior to reading anything about it, to experience the surprise of its arcs and turns properly. And then warrants watching again, a second time, to experience the horror of what you already know it’s leading up to. Please watch it before (or instead of) reading this next part, because there are spoilers ahead.

Nanette begins as a conventional stand-up show. In the first act, Gadsby cheerily shares a bit of audience feedback, that her previous show didn’t contain enough ‘lesbian content.’ “I was on stage the whole time!” she quips. She revists her first ever show (“classic new gay comic 101 - my coming out story”) and tells a condensed version of one of her routines - an encounter with a man at a bus stop who turned aggressive and homophobic when he believed Gadsby was hitting on his girlfriend, before inexplicably changing his demeanour upon realising she was a woman. She also talks about how she has ‘forgotten’ to come out to her grandma, and tells an anecdote about deflecting a question about finding ‘Mr Right’ because she “doesn’t have time.” This whole section gets laughs, Gadsby punctuates each joke with a cheeky grin. It’s a consummate comic performance.

She then declares, quite earnestly, that she has built a career out of self-deprecating humour, and now wants to quit comedy. “Do you understand what self-deprecation means when it comes from someone who already exists in the margins? it’s not humility, it’s humiliation. I put myself down in order to seek permission to speak.”

And so begins the second act, which serves as a deconstruction of comedy, how so much revolves around the differences between men and women, and which groups seem fair game as target. (A particularly droll highlight: “Do you know why I love telling jokes about straight white men? Because they’re such good sports!”)

Jokes, Gadsby argues, are made up of a set-up, which introduces tension, and a punchline, which releases it, producing laughter. “Tension isolates us, laughter connects us.” The comedian makes their audience tense, and then makes them laugh. “This is an abusive relationship!” Furthermore, in order to produce a laugh, jokes often omit the end of their stories. Throughout her career, Gadsby has omitted the ending to numerous stories that were often both formative and traumatic, to make other people laugh. “You learn from the part of the story you focus on, and I need to tell my story properly.”

This is the third, final, devastating act.

Gadsby launches into a passionate polemic on structural sexism, then revisits the bus stop anecdote, this time continuing beyond the original punchline. In reality, it didn’t end with the bigoted man leaving, amusingly baffled, but with a harrowing homophobic assault, which she didn’t even so much as report because she was ashamed. Gadsby lets the audience stew in their pin-drop silence. “And this tension is yours, I am not helping you anymore. You need to learn what this feels like, because this tension is what not-normals feel like all the time.”

There has been significant amount of tedious pedantry over whether Nanette technically qualifies as ‘stand-up’, because the third act isn’t funny. Deliberately so. But that’s exactly why it is stand-up, it wouldn’t work otherwise. It’s a stand-up routine with the tension-diffusing punchlines removed, a subversion which lays bare the trauma implicit in so much comedy. It forces a captive audience to confront what they were laughing at, who they were laughing at, and who they were to laugh at it.

The show crescendos into a supremely well-crafted and uplifting invocation against anger. During her final routine, Gadsby declares: “To the men in the room who felt I may have been persecuting you this evening: well spotted! That’s pretty much what I’ve done there. But this is theatre, fellas. I’ve given you an hour, a taste. I have lived a life. The damage done to me is real and debilitating, I will never flourish, and this is why I must quit comedy, because the only way I can tell my truth and put tension in the room is with anger.”

The story about the kid who ripped me, ostensibly for having too-small trousers, didn’t end at the point of my mild comeback. He waited for me after school and kicked my head in. I’d taken beatings before, but took a perverse pleasure in this one. It’s strange to say, but I think I was proud that I’d humiliated him so badly he wanted to beat me up. He was pathetic, and I had power over him.

There are crucial differences between myself and Hannah Gadsby. For a start, she’s a professional comedian, and I, at best, managed to amuse my bored classmates. Second: being self-deprecating is fundamentally different when you’re not a straight white man, this seems a trite and obvious point, but I’m not sure I’ve considered this enough in my life.

I spent my youth mocking myself so that I had permission to speak. I made fun of being ginger, because it was accepted that this was a grotesque physical trait. I developed a skill for using the fact that I was short and built like an emaciated Peperami Man, all the while secretly resentful that my body refused to grow, regardless of how much protein powder I forced down. I told everyone I was the richest man in Wales because I was decidedly not rich. I played to swipes at being perceived as effeminate, and milked my cack-handed clumsiness (latterly diagnosed as dyspraxia.)

I turned my teenage self into the caricature of a weirdo sexless goblin boy that I was sure everyone saw me as, and at times it felt brilliant to soak up the laughs. On other occasions, it was crushing. I couldn’t be anything around people other than ‘funny’, and that involved positioning myself as low-status dirt beneath their feet.

As I grew, the insecurities that brewed in the furtive cauldron of my teenage bedroom evaporated. Turns out - surprise, surprise - beyond the schoolyard, you rarely get much abuse for the way you look as a straight, white adult male. We don’t get targeted for physical intimidation and assault on account of the way we look. People don’t carry out campaigns of calculated violence against straight white men.

Self-deprecating humour warps your sense of perspective: positioning yourself as low-status seemingly means you have carte blanche to make fun of everyone else. The jibes can’t really hurt, because, hey, look who’s saying them: me - a weirdo sexless goblin boy!

Of course, this power dynamic is completely skewed if that weirdo sexless goblin boy is a straight white man. Even if what they’re saying has nothing to do with race, or gender, or sexuality, it’s not the same. Of course it isn’t, obviously. But if your race, gender or sexuality isn’t that of a straight white man, and you want to make people laugh, then you better come armed with an arsenal of excoriating jokes which all take aim at that.

When former Never Mind The Buzzcocks team captain Sean Hughes passed away last year his friend Michael Hann wrote a eulogy that attracted controversy for being entirely too soon, and not entirely complimentary. Writing of his late friend, Hann said:

“It’s hard to write about Hughes, not just because he had been my friend, but also because my memories – like many other people’s – are not all positive. I can laugh about the time at a Cure aftershow party when he tried to convince people he was the estranged nephew of far-right Austrian politician Jörg Haider, but I can also recall his unerring eye for other people’s weakness and insecurity, and his willingness to deploy it.”

He paints Hughes as a volatile, troubled character who alienated many of his closest friends. The honesty of it hit me like a ton of bricks.

Never Mind The Buzzcocks is a show which thrived on comedic cruelty, and one I - like many people - absolutely loved as a prepubescent. I wanted to be as acerbic as Hughes, or Mark Lamarr, or Simon Amstell. Having an unerring eye for other people’s weakness and a willingness to deploy is a trait championed as admirable by generations of panel shows.

My teenage adoration for these sorts of shows lead to tendencies that aren’t entirely pleasant. I loved the sport of people coming up with stinging lines about me and responding quickfire with similarly barbed words, directed at myself - the goblin. But, when you’re someone who’s good at exploiting your own shortcomings for yuks, chances are you’ll eventually get pretty good at clocking everyone else’s too. To my mind, this subsequent mockery was a term of endearment, like on Buzzcocks.

It’s disconcerting to me how it wasn’t until into my twenties that I made the connection between the (obvious, when Gadsby points it out) humiliation of self-deprecation, and that I was extending that humiliation to people I wanted to enjoy being in my company.

A few years ago, I went through an embarrassingly juvenile stage of cheerily greeting everyone with “hello, you c*nt!” in a chipper voice. I was saying the rudest word in the politest way, so I seemed like a wretch, but a delightful one. People would laugh. But one time I did it to a dear friend, and she didn’t laugh. Later she confided that she had been, unsurprisingly, upset by being called a c*nt. I was mortified. I had subjected her to a stupid bit of unfunny banter and decided because I didn’t have a problem with the word, no one else should.

It’s painful to contemplate how my adolescent self believed that unkindness could be a form of kindness, and how oblivious I was to making someone feel small. It’s worse still to consider that this tendency probably still lurks within me, closer to the surface than I’d like. Part of me wants to justify aspects of it, that if the power balance is right, it’s acceptable. After all, when I was getting my head bashed in after school, there was only one person punching down.

If that is the case, there needs to be far more of a concerted effort to acknowledge those power dynamics, and to examine our relationship to comedy, on the part of people like me, and maybe you.

Do we want to watch stand-ups humiliate themselves? Are they supposed to facilitate our cruel impulses by vocalising them themselves, about themselves? Do they even want to? Is certain types of comedy turning us into masochists?

Nanette should absolutely be considered a stand-up show. It’s supposed to replicate the experience of what it’s like to attend a comedy show that leaves you feeling uncomfortable and not laughing. I hope we all see something like it again very soon.

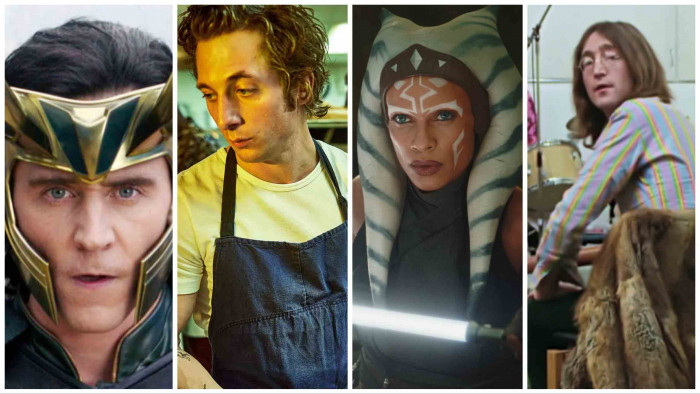

(Image: Netflix)