"I didn't have the tools to know why I was in so much pain": Jordan Stephens on the trouble with being a man

The actor and former Rizzle Kicks rapper thinks we're getting masculinity wrong

James Bond is no hero. Just ask Jordan Stephens; he doesn’t want you to fall for 007’s bullshit.

“He’s a womanising murderer who has spent 27 films running away from his childhood trauma,” says the writer, actor and former half of hip-pop duo Rizzle Kicks. “I grew up in a world idolising role models like James Bond, one where we’re told we have to be strong the whole time, and that it’s weak to cry or show vulnerability. And I think that’s a big problem for young men.

“Take the way 007 treats women. I mean, there’s a scene in Skyfall where he literally has a conversation with a woman who tells him that she was a child sex worker and then about three scenes later he sneaks up on her in the shower, nothing said.”

Stephens doesn’t mince his words. And right now, the 26-year-old is making a point. “When you don’t have enough alternatives in popular culture for young men to measure up to, they will internalise that kind of misogyny. When I was growing up, there was a lot of popular culture that subtly pushed this idea of women, or female energy, being inferior. It was as if perceived feminine qualities in men – like showing emotion – were a sign of actual weakness. That shit stays with you, man, whether you know it or not.”

We’re here, in a photographic studio beneath ShortList’s London offices, to talk about Britain’s masculinity crisis. Or, as Stephens has put it: “a toxic notion of masculinity being championed by men”. Let’s be clear, this is not an attack on men but on one of masculinity’s many voices. It’s just the voice that too often shouts the others down.

It is the dark corner of male culture that teaches young boys to be embarrassed about their emotions and to strangle them at birth – unless that emotion is anger. It is the same corner in which men are taught they don’t have to ask permission to act on their sexual desires.

Are we sending men into life over-armed and under-briefed? How many times have you been told to “man up” or to “grow a pair”? Have you ever called another man a pussy for not wanting to climb a tree, or fight? The effects of such language, says Stephens, are pernicious and long-lasting.

“I’m not saying there isn’t a place for strength or risk-taking or competition in male culture,” he says. “But we shouldn’t be ashamed of showing our vulnerabilities, either. I mean, from my experience, whenever I’ve got really depressed or really sad or felt suicidal it has been when I felt ill-equipped to love myself and to share my pain.”

Stephens grew up on a housing estate in Neasden, then Brighton. Like so many only sons, he felt obliged to fill the role of “man of the house” – a futile, not to mention draining exercise for a boy of nine. “A lot of my traumas now, come from that period,” he says. Without an outlet through which to jettison those emotions, he bottled them up and stashed them in the cellar of his mind.

It was sometime in early 2014 when it happened, though Stephens can’t say exactly when. Rizzle Kicks had already sold more than one million singles, and their second album, Roaring 20s, had just been released to critical acclaim.

He seemed to have it all: money, success, women, fame and validation. He was, as other men would sometimes tell him, ‘The Man’.

So when the death of his elderly grandmother followed soon after the suicide of a close friend, he dealt with it accordingly: “Like a man. I put myself into a place where I could completely disconnect from my emotion,” he says. “I just put a lid on it and pretended it didn’t exist.”

He didn’t share his pain with anyone because that’s not, of course, what “real men” do. Instead, he searched for solace in the bottoms of bottles and baggies of cocaine. It didn’t help.

For the next three years, old wounds, the pressures of fame and a skewed interpretation of manhood conspired to squish him deeper down the rabbit-hole of self-destruction. Knowing he needed help, he turned, not to his friends or his new girlfriend, but to Google.

“I didn’t have the tools to understand why I was in so much pain, so I was Googling stuff like: ‘Can you be in love and depressed at the same time?’” he says. “I just ended up sabotaging myself – more drink and more drugs. And in the end, it cost me my relationship. I had fallen into a place where I saw self-sabotage and chaos as a home.”

Read more: What do you do when the most visible men in the world are arseholes?

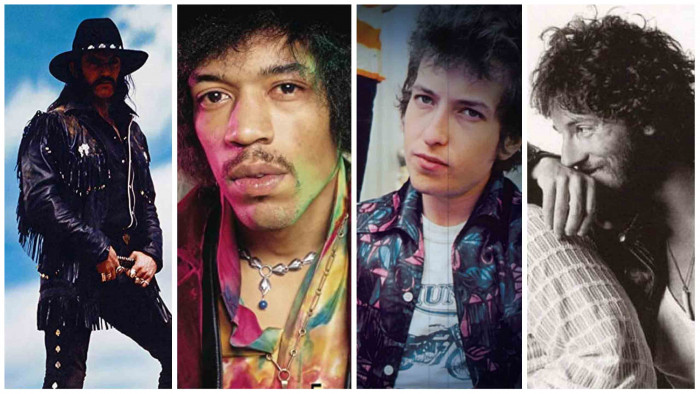

Jordan Stephens in his Rizzle Kicks days

Newly single – and in fear of his life – he tried something new. He quit drink and drugs, sought therapy and set out to untangle the spaghetti bowl of anxieties that had haunted him for so long.

“I realised I was taking a lot of my anger out on myself, partly through addiction. When it came to relationships, I would project my own angst on to people, without having the maturity to just ask for what I wanted. Instead, I’d throw my toys out of the pram rather than have an adult conversation.”

These days, he says, he feels closer than ever to “a place of contentment and responsibility rather than chaos and immaturity”. Now he wants to talk about masculinity. “I don’t want young men to fall into the same trap,” he says. “I don’t believe there’s a person who gets any good feeling from treating other people like shit. Often, how we treat others is, in fact, how we treat ourselves.”

The pressure to conform to modern culture’s outdated stereotypes is a burden on many young men. It narrows their lives and contaminates their happiness. Is there an answer? “Men need to understand that this isn’t about destroying masculinity or shaming men just for being men,” says Stephens. “It is time for the responsible, sensitive, strong among ourselves to step up and cast away these degrading, oppressive messages that we’ve filtered into our culture for so long.”

What it all really comes down to, he says, is one thing. “I think the quality that has been most neglected by men is the most important thing that we have: connection. That is what makes us human. And without it, the world can be a very lonely place.”

(Photography: Conor Clinch)